|

For more than a decade I ran an Entrepreneurship Centre helping thousands of clients each year and I’d now like to apologize to them. At the time, it was common place to promote and teach business planning as a start-up best practice. In fact we eventually built our entire service offering around the business plan and the individual components of a fulsome plan. We didn’t know any better. I started having doubts about this strategy when I learned that banks were making moderate sized business loans based almost solely on the applicant’s ability to pay back the loan, not on a critical assessment of the business plan. Similarly to a car loan, you could get a business loan if you had a good credit rating and history; the bank manager didn’t test drive the car to determine if you were buying a lemon, they were simply concerned about your ability to pay back. At the same time I began to collect a lot of evidence that suggested that most successful business owners had not in fact written a business plan – at least not in the early days of their new venture and many of them were returning to the Centre years later to now write one. It seems there are a number of issues with business plans that we had previously overlooked (an oversight that many are still making today): 1. A really good (seemingly) business plan could be written without ever talking to a potential customer. Many great business plans are simply not based on any market need, justification or reality – but they read really well! Case in point: see any number of prize winning business plans submitted at business plan competitions, most never coming to fruition. 2. Good business plans include actions plans, implementation time lines and concrete strategies; in other words, an execution document. These are all valuable and necessary tools, but an early-staged business plan is usually based only on speculation about the market, client needs, buying cycles etc. As such, these seemingly good action plans and strategies are (again) not based in reality and tend to waste a lot of time and resources when the entrepreneur tries to implement them. 3. Well-articulated and well written business plans are often used as a proxy for good business ideas. Good plans often disguise as good potential businesses, but in reality most written at an early stage are merely a work of fiction, at best a quality research paper not based on actual knowledge of the market or client interaction. Like winning in sports, you need to do it to be good at it – you can’t just learn about it and plan for it in isolation of actual experience. All the information and data you need to start a good business needs to be gleaned the old fashioned way – talking to customers, suppliers, and other key industry players then crafting a viable solution based on real needs. There is also a fair amount of trial and error involved in getting to a viable business. Most businesses will adjust (pivot) with experience so the plan is likely wrong before it’s even written. We need to pay a lot more attention to business models vs. plans at an early stage. Business plans are usually taught and written much too early in the process. Entrepreneurs need to concentrate first on getting the model right (www.businessmodelgeneration.com) and validating the customer problem/solution fit (http://steveblank.com/2009/06/25/convergent-technologies-war-story-1-%e2%80%93-selling-with-sports-scores/) before starting on the business plan. There is still a valuable place for business plans – it’s just not as soon as we once thought. As educators and coaches, we need to direct early staged entrepreneurs away from business planning and towards: talking to customers; learning and adjusting; and, building profitable, scalable business models. The business plan can wait until they actually know what they should be doing! The message is clear: entrepreneurs create jobs and stimulate economies, at the same time, more of our future leaders are interested in pursuing entrepreneurism. New economic realities and student interest are driving growth in the area of entrepreneurship support and capacity building; this growth is creating strategic advantage for recruitment efforts, student success, fund-raising activities and regional economic development. Based on the ongoing review of research, survey results and best practices, the following broad success factors have been developed as a “best case” template in building a best-in-class campus entrepreneurship support ecosystem:

1. Leadership and Strategy– First and foremost, there needs to be palatable support for entrepreneurship capacity building at all levels, especially the most senior. Entrepreneurship support initiatives must be more than a “new program.” The promotion of entrepreneurism and support for student ventures must be incorporated into strategy, policies and procedures across the institution. In addition, the leader of entrepreneurship initiatives must be adept at dealing within an academic institution, yet also be uniquely qualified as someone who is familiar with entrepreneurship and building the conditions that lead to entrepreneurial success. 2. Funding – There are two parts to funding: first, sustained and sufficient funding for entrepreneurship support; all successful projects require appropriate capacity and funding for supportive projects and initiatives, not just funding for the efforts of one individual. Second, funding to support student ventures is a key ingredient and should likely include some combination, or all of: micro financing programs; access to angel and venture capital networks; and, seamless path finding to available grants and loan programs. 3. Community Engagement – Key to the success of any new venture is access to relevant communities which might not be easily accessible. Most student entrepreneurs don’t have experience with, or connections into, these networks. Formal and informal networking opportunities are required for students (and faculty) to link to and learn from potential clients, collaborators, strategic partners, professionals and suppliers. 4. Mentoring – Linked to community engagement, but important enough to have its own category, is mentoring. As with industry and professional networks, students don’t often have deep connections to the key individuals who can guide them along the entrepreneurial path. Formal mentor programs provide great opportunity for alumni involvement and community engagement. Interesting to note that in the most recent Princeton Review of the best Campus entrepreneurship programs, the top 25 institutions all had multiple mentoring programs. 5. Incubation – While a physical incubator or space is not essential, the benefits are very attractive. A formal incubator or “co-location” space provides for a leverage point for recruitment of students and funders, a focal point for broad cross-campus entrepreneurship initiatives and an opportunity for like-minds to benefit from the energy, synergies, competition and peer learning that often spurs great innovation. 6. Learning – Entrepreneurship courses are different than business courses. Entrepreneurship courses cannot just be re-purposed or rebranded business courses they must have a focus on early-staged, entrepreneurial ventures. Also vital to a healthy entrepreneurship ecosystem is the non-credit learning available to students to include personal development, guest speakers and activities & competitions that provide experimentation and skills development opportunities. 7. Celebration – The promotion of the available opportunities and capacity, as well as the public celebration of success is key to long term sustainability. All stakeholders need to be well informed and engaged in the ongoing successes and activity of the initiative. Proactive communications and celebrations are vital for student recruitment, fund and sponsor development and for the student entrepreneurs and their business success. Many practices, best and otherwise, have provided an opportunity to learn and adapt. While some have a head start on entrepreneurship programming and branding, many are playing catch-up. On a positive note, many worthwhile initiatives can be implemented quickly and efficiently with lasting impact. However, speed of implementation is key to gain mind share on campuses and provide economic impact in communities. It’s no surprise that global leaders are increasingly looking at entrepreneurship as a way to grow jobs and stimulate economies. The fact is, approximately 68% of net new jobs are created by small and medium sized enterprises. The reality is that large firms shed jobs and new firms – startups run by entrepreneurs – drive job growth. The question becomes: What are we doing to stimulate interest in entrepreneurship and provide support to entrepreneurs? Some would see this as an opportunity not to be missed.

Supporting this opportunity is the growing interest by young adults in entrepreneurship as a career choice. A Kauffman-funded study of youth aged 8-21 cites 40% of respondents as interested in entrepreneurship as a career option. In the past few decades, we’ve seen this play out at colleges and universities with the number of entrepreneurship courses rising dramatically. A 2009 study by Professor Menzies of Brock University points to a 33% increase in the number of entrepreneurship courses between 2004 and 2009. And this wasn’t just the beginning of the entrepreneurship wave, the previous 20 year’s growth rate tallied in the hundreds. More than just courses, we see an increase in the number of University and College based entrepreneurship centers along with the capacity to support students in their entrepreneurial ventures. We see everything from fully-funded and staffed physical centres offering a full range of services to virtual clusters of non-coordinated and informal entrepreneurship support activities. The message is clear: entrepreneurs create jobs and stimulate economies. Students’ interests are driving growth in the area of entrepreneurship education and this growth is providing strategic advantage for recruitment efforts and fund-raising activities. What better place to leverage this important economic lever than in supporting start-up activity on campus, during a student’s academic career? While many are discussing, studying, analyzing and debating, others have put a stake in the ground and declared that teaching entrepreneurship as a viable career option, and the skills that go with it, is an economic imperative.

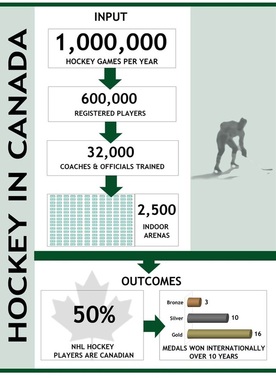

In a recent article, China Daily reports that the government of China has ordered Universities “to start teaching basic courses on entrepreneurship to undergraduates to encourage students to start businesses and become self-employed after graduation.” (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2012-08/28/content_15714073.htm). Similarly, the EU passed legislation years ago to ensure that entrepreneurship was being taught in schools – as young as primary schools. See:http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/promoting-entrepreneurship/education-training-entrepreneurship/index_en.htm. Some specific examples include: - In Bulgaria, the new Law on Pre-school and School Education, still under discussion in ministerial working groups, envisages entrepreneurship, creativity and developing a sense of initiative as one of the main goals of the educational system in Bulgaria. Entrepreneurship will be included as one of the subjects to be introduced. While the Ministry determines at national level the total number of hours for this area of the curriculum, schools are free to decide how to distribute these hours between a range of subjects. - In Ireland, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment has developed a short senior cycle course on enterprise. It has not yet been incorporated into the curriculum; its implementation is still under discussion between educational stakeholders. - In Spain, the 2011 reform of the core curriculum for lower secondary education includes a new optional subject in the 4th year Professional Guidance and Entrepreneurial Initiative. The reform will be implemented in 2012/13; nevertheless, the education authorities are free to implement it from 2011/12. - In Cyprus, in the new curriculum for primary and secondary education to be implemented in school year 2011/12, emphasis is given to attributes, skills and working methods that enhance entrepreneurial behaviour as a cross-curricular objective. - In Malta, a draft National Curriculum Framework (NCF) was launched in May 2011 as a consultation document. Education for entrepreneurship is proposed as a cross-curricular theme identified as essential for the education of all students and for achieving the aims of education. It is intended to strengthen the embedding of elements of entrepreneurial behaviour through the integration of entrepreneurship programmes, projects and activities in the established curriculum for schools both at primary and secondary level. - In Poland, the ongoing curricular reform which will be completed in 2016 focuses on shaping attitudes and competences including entrepreneurship. - In Sweden, entrepreneurship is part of the ISCED 3 school reform implemented in 2011, in the form of commentary material on how to look at entrepreneurship in the various programmes, and in the form of a forthcoming commentary material on the new subject of entrepreneurship, which will be published in 2012. - In Iceland, national curriculum revisions were launched in 2011 and new subject curricula are expected in 2012. These revisions will include compulsory elements of creative activity for all subjects. The question becomes: what are you (we) doing to encourage and nurture entrepreneurs? Where will my Country/State/Province/City be positioned economically 10 years from now when kids from around the world graduate having spent their academic careers being encouraged into, and learning skills supporting, entrepreneurism? What is needed is more action, capacity and certainty around programs, policies and initiatives. Credit to initiatives and organizations that are working to make a change, including Start Up Canada, the Ontario Jobs and Prosperity Council and OCE’s Experiential Learning Program, though we need to move from talking and planning, or in OCE’s case – piloting – to action mode and long-term program commitment with respect to on-the-ground promotion of entrepreneurism and support for entrepreneurs. We are clearly losing out to other Countries in this area and the time for action and commitment is now.  Hockey Excellence: Lessons for Entrepreneurship? Original post NOVEMBER 7, 2012 http://economicdevelopment.org/2012/11/hockey-input-outcomes-lessons-for-entrepreneurism/ In Canada we produce great hockey players. In fact Canadians comprise 50% of all NHL players and Canadian national hockey teams have won 29 Gold, Silver or Bronze medals on a world stage in the last 10 years. It’s pretty impressive! When we look at the success factors that got us where we are today in the sport we see a number of things that have contributed to this dominance: - a culture that supports and encourages hockey; - a continuum of skills training at the earliest of ages and at every skill level; - more than 2,500 indoor hockey rinks and tens of thousands of outdoor rinks; - approximately 32,000 coaches and officials trained each year; and, - at least a 1,000,000 organized games and scrimmages played each year. (Source: http://www.hockeycanada.ca/en) There is a reason we excel and achieve success – simply put, we’ve built the support infrastructure and capacity to succeed. When we look at our positioning on a world stage related to entrepreneurship, we have to admit that those same success factors simply don’t exist. In fact, the success factors would look very similar: - a culture that supports and encourages entrepreneurism; - a continuum of skills training at the earliest of ages and every skill level; -thousands of experiential learning opportunities; - tens of thousands of teachers and mentors that can build awareness and skills; and, - a million opportunities to start businesses and learn from failures and successes. The reality is we have not built the required support infrastructure and capacity to achieve entrepreneurial success on a world stage (i.e. the type of economic success driven by new, small and medium sized businesses.) The required infrastructure and support isn’t developed over night, it took us decades to put in place the hockey development program that results in our ongoing success and it will take us some time to do the same for an Entrepreneurship development program. We need to start promoting entrepreneurism as a viable career option and teaching business skills as early as possible. We wouldn’t tap a 24 year old on the shoulder and ask them to learn how to play hockey so we can compete internationally, why do we think it would work for entrepreneurism? We need to start building out the entrepreneurship support continuum and infrastructure. My thoughts on establishing some preliminary steps can be found at: http://agawacorp.com/excerpts-from-agawas-sumbission-to-ontarios-mtcu/. |

Stephen DazeContent related to building capacity to promote and support entrepreneurism. Archives

January 2020

Categories |

COPYRIGHT 2015 © coachmystartup

RSS Feed

RSS Feed